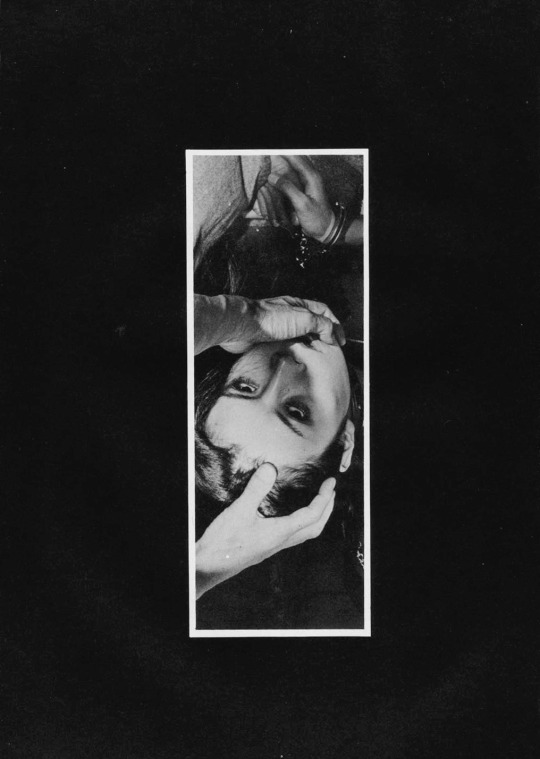

Yan Bertoni – Emma #3 (2017)

This is a visually arresting image–without a doubt.

Were one so inclined one might talk about color (The palette of red hair to ochre lichen to the brackish algae tinged lake) or about texture (the lack of texture in Emma’s skin and the surface of the water vs. the abundance of texture in the wooden dock).

I–for my part–can’t look at it and not compare it less than favorably with Chadwick Tyler’s effing exquisite image of Cora Keegan from back in 2014.

The fact that I prefer one to the other probably won’t surprise anyone who has been following this project for any period of time. The reason why I prefer one over the other almost certainly will: I think the above image is over-composed to the point of sterility.

What do I mean? I mean this isn’t strictly governed by the rule of thirds. I charted it for you to peep:

What is interesting is that if you zoom in a bit and ignore the water the dock conforms to the rule of thirds:

This sort of nesting of for frames within frames reminded me of the Golden Ratio. So I diddled around with that for a bit. The image in no way conforms to it but imposing the spiral in on particular way does illustration something about how the image is arranged to cause your eye to track back after it has moved all the way from left to right:

Well, I mean… that all sounds pretty sophisticated when I lay it all out there. So why do I prefer Tyler’s image?

Well, I don’t think the golden ratio overlay is a function of calculations in the making of the image. More: I think that the golden ratio is everywhere. Yes, it’s rare to find an image that conforms to it to a T but I think the rule of thirds works because it takes the ordering principles of the mean and parses them in such a way that you can achieve a similar effect without measuring with painstaking exactness. I’d wager there’s very few thoughtfully composed images that can’t be argued demonstrate some implicit reliance on the golden ratio.

What makes Tyler’s image better is that well–there’s little if anything to stop someone with a decent camera, time and a little bit of money from recreating Bertoni’s image. While I will grant that the model will be slightly older and the reflection of the sky and the weathering on the dock might have changed slightly–it’s not a question of whether or not it can be done, more a question of whether or not the person doing it has the patience to do it.

How would you even begin to go about recreating Tyler’s image. Go ahead, I’ll wait.

When I say sterile that’s partly what I mean. Bertoni’s image has been so rigorously balanced it has no life left to it and as such there’s nothing distinguishing it as singular or unique. (Also, I’ve seen other pictures from this series and the dock here is like six feet off the water–which you can’t tell given the image.

Also, what is Bertoni’s image about? A model posing for a photographer. There’s little else as far as suggestion of a narrative.

Whereas with Tyler’s image: why the hell is she smoking with her head hanging off the dock? Does she not want her face int he shot. Is her hair in the water? Is this a model posing for a photographer or is it two friends hanging out one with a camera and another just fucking around and then there just happened to be this wonderful accident of a masterpiece of a shot.